Reliving the remarkable rise (and demise) of Death Cigarettes

He’s the fearless entrepreneur behind one of the most controversial brands the UK has ever seen. But a little over two decades since he took on the tobacco establishment, BJ Cunningham still maintains that it’s unfair to label Death Cigarettes as ‘provocative’.

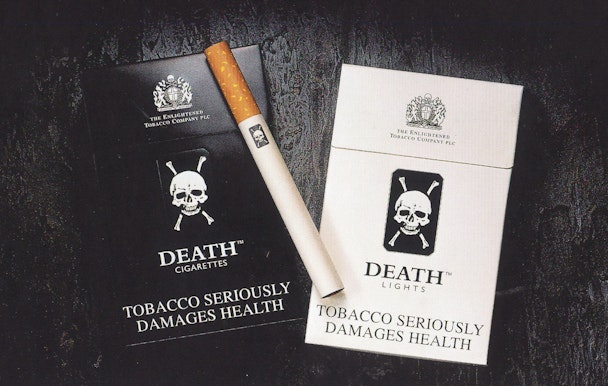

Death Cigarettes

BJ Cunningham sits back, takes a drag on his cigarette, and begins to recount the tale of how he went from being £876,000 overdrawn in a one-bed Lewisham flat to running arguably the most controversial brand the UK has ever seen, leading diplomats from Spain and Portugal in a crusade against tax laws at the European Court of Justice.

This is the story of the life and death of Death Cigarettes, a brand quite unlike any other.

The story begins, as many of the best do, in a bar. It is the early 90s and Cunningham is, as he puts it, “bust”. “I was in Los Angeles with a mate and we were laughing at the lies that go on in advertising… wouldn’t it be funny if there was a beer called Pissed or a butter called Coronary or a cigarette called Death? We laughed about Death Cigarettes and the next day when I woke up I was still laughing. I decided there was something in it.”

First, Cunningham had to resolve the small matter of his gigantic debt. “I said to the bank, ‘If you’ll take my current debt and write it down as £250,000 and lend me a further £250,000, I’ll pay you back the £500,000 over three years based on this idea’ and… God bless Barclays, they backed me.”

The improbable agreement was laced with a single, crucial caveat – Cunningham had to secure a manufacturer willing to make his drunken dream a reality.

“I went to see Gallaher, one of the largest tobacco companies in the UK, and had the shortest meeting of my life. When I put my mock-up packet on the table, he picked up the phone and said ‘Security’.”

It took a moment of serendipity to save Death from an early grave, and six months after that ill-fated meeting Cunningham found himself once again setting the world to rights, this time in a café in Amsterdam.

“I was sitting opposite this lovely bloke and the conversation came round to ‘what do you do?’ He’d just inherited a cigarette factory from his father and at the same time found religion, and was having a hard time reconciling his new-found beliefs with the manufacturing of cigarettes. So I offered him the opportunity to profit from the truth with Death Cigarettes and he said ‘amen’. Next thing I know, my one-bed Lewisham flat is full of fags.”

Death was finally born in 1991, and the controversy soon flowed. After Gallaher, Cunningham anticipated hostility from the tobacco giants, but he sounds sincere when he says he didn’t expect it to upset everybody else. “Weirdly, the anti-smoking lobby took issue with it. The tobacco industry took massive issue with it. The government took massive issue. It was really beautiful to sit on the moral high ground.”

23 years on, Cunningham still thinks it’s unfair to call the brand provocative. “I think it’s provocative to call a brand of cigarettes Camel or Marlboro or anything else. In fact, the least provocative thing a cigarette should be called is Death, given that it’s the only legally available consumer product that kills people when used exactly as intended.”

Death’s main source of exposure, unsurprisingly, was PR – but the press had sharpened their daggers too. The brand sponsored the life-saving quadruple heart bypass of a British man refused treatment because he was a smoker. At a press conference, a Daily Mirror journalist asked: “Are you not just cynically exploiting this man’s life in order to promote your brand of cigarettes?” Cunningham’s reply was legendary: “Yes, that’s exactly what we’re doing! Don’t you think it would be more cynical to let this guy die?’”

With its brutally honest intentions, Death established a loyal customer base. “We were able to create a movement because smokers still are a scapegoated minority, even though they contribute billions to the economy. The point was never just to shock; the point was to make money, and we did that very successfully when we could sell cigarettes.”

And that was the toughest challenge of all. “I realized pretty early on that it doesn’t matter how much people want your product or how involved they are in your story, if they can’t buy it, if it’s not on the shelf for sale, you can’t sell it. The shelf was owned by the major tobacco companies and they didn’t want to see the skull and crossbones next to their product. They felt it was antithetical to their interest and did everything in their power – which is substantial – to stop it. And mainly their power is in distribution.

“It doesn’t matter if you’ve got the most brilliant marketing idea in the world, because you have to have the distribution, the finance, logistics, all of it.”

In the end, Death’s demise came at the European Court of Justice in 1997, challenging legislation to restrict it from importing cheap tobacco. By proxy, it was taking on a UK government determined to protect its £9bn-a-year revenue from domestic cigarette sales. “The French judge reasoned, ‘You are right in law, but the law was never intended for you to be right and therefore you are wrong’.” To the glee of its numerous enemies, this would be the brand’s killer blow.

If Cunningham had his time again, would he relive Death? “Without a shadow of a doubt. It’s the best journey in the world. Every day you wake up alive.”